What Are Caring Contacts?

There’s a pressing need to quickly adopt scalable, evidence-based approaches for preventing suicide.

There’s a pressing need to quickly adopt scalable, evidence-based approaches for preventing suicide.

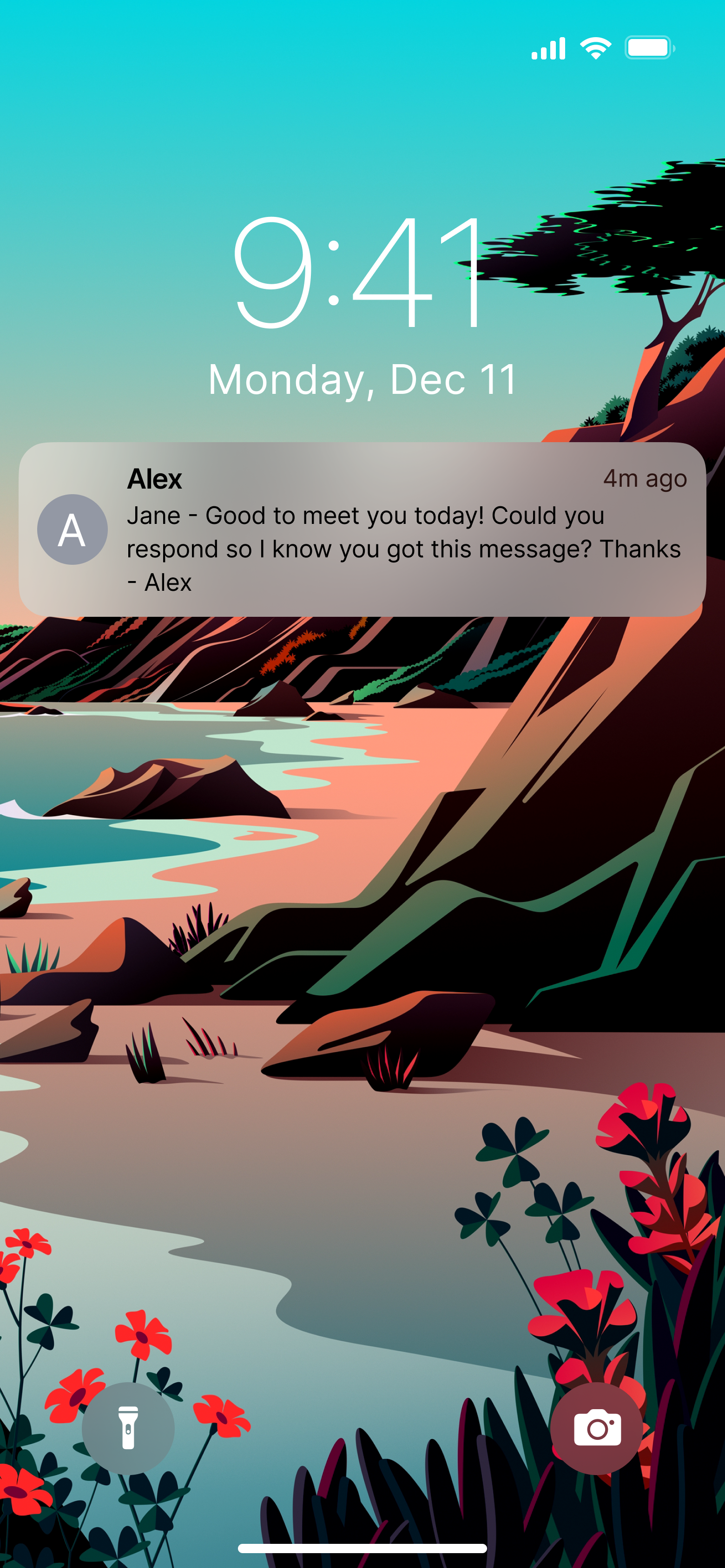

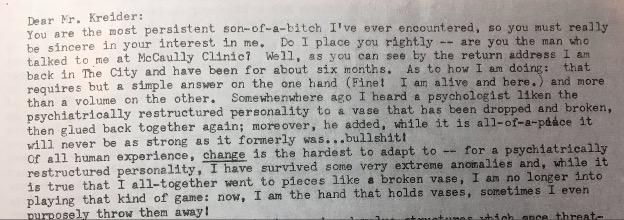

Caring Contacts (CC) is one of only two interventions that have been found to prevent death by suicide in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The original Caring Contacts intervention was developed by Jerome Motto in the late 1970s and guided by four principles.

The forces that bind us willingly to life are mostly those exerted by our reciprocal relationships with our environment and the beings in it, whether they be intimately involved in our lives or influence us by other psychological processes.

A suicidal person can be encouraged to retain an interest in continued living, by regular and long-term contact with another person who expresses caring about the former’s wellbeing.

The contact must be initiated by the concerned person and must put no demands or expectations on the other, in order to be experienced as an expression of unconditional concern and to have a potential for reducing feelings of isolation and helplessness.

Such a program of continuing contact can exert a long-term prevention influence on high-risk persons who cannot accept the established health care system or who have unmet needs. Long-term follow-up from an RCT comparing Caring Contacts to treatment as usual (TAU) found participants in the Caring Contacts condition had a lower suicide rate in all five years of the study and a significantly lower rate for the first two years.

Image credit: Jason Cherkis, Huffington Post, November 15, 2018. “The Best Way To Save People From Suicide”

The importance of continued, long-term contact is evident in this image of what Motto referred to as “the bingo letter.” The participant in Motto’s trial who wrote this 5-page, single-spaced, typed reply to researcher Douglas Kreider had, 18 months earlier, written what Motto described as a “kiss off” letter to Mr. Kreider—basically an “I’m fine, thanks” response. In this subsequent letter, it is clear that the repeated and long-term quality of the letters was—at last—making an impact.

Feeling suicidal is so much about feeling alone and feeling this will never change. Caring Contacts arrive periodically—weekly, monthly, bi-monthly—over a year or longer showing continued care, interest, and support with no effort from the recipient. Caring Contacts participants report that messages continuing to come over time have been healing for them.

Caring Contacts can also be a bridge to help someone ask for help who would not otherwise have asked. It is not uncommon for someone to reply to their 8- or 10-month Caring Contact with a request for help, resources, or a pathway back to treatment that ended months before.

Caring Contacts can be offered as aftercare following safety planning or hospitalization and has been used successfully with recipients from a variety of backgrounds - military, veteran, youth, native communities, primary care and emergency departments, healthcare providers, etc. - from around the globe including the US, Australia, and Iran.

Feedback from previous recipients

“I actually enjoyed it, because I knew it wasn't just a computer, it was an actual message.”

“[The messages] made me value life more. Because life is valuable. It really is.”

“It helped me boost my confidence. When I was feeling down, there was somebody thinking of me and it made me feel better about myself, made me move forward. That's what those messages helped me with, gave me strength.”

“It was a good feeling to know that somebody is actually out there. Somebody thought about you today and decided to check on your wellbeing... it helped me to understand there are people that care out there. It's not just me by myself, that it's okay to talk to someone that I don't have to keep it all bottled up.”

Caring Contact messages are sent to a recipient in a way that does not allow the participant to respond to the message. (e.g. one-way text messages, letter that do not invite a reply, emails sent from a “do-not-reply" email address)

Caring Contact messages are sent to a recipient in a way that gently invites and allows the participant to respond (if they choose to) and converse with the author of the Caring Contacts. (e.g. 2-way text messages, letters that invite a reply)

2-way Caring Contacts texts and Caring Contacts sent via postal mail have evidence of efficacy, but in practice 1-way Caring Contacts texts have been more commonly used given their relative operational simplicity. To date, research on 1-way Caring Contacts texts remains limited and the benefit of delivering 1-way Caring Contact texts remains unclear.

Despite promising evidence for the Caring Contacts intervention, few health systems are using Caring Contacts today. In addition, some have made maladaptive modifications that weaken core Caring Contacts principles, limiting fidelity to Motto’s 4 Core Principals of Caring Contacts and the evidence-based version of the intervention. These maladaptive modifications occur largely because the steps to carry out the intervention often fall outside of established workflows. There has not been an easily accessible guidebook for how to plan and deliver Caring Contacts with high fidelity, until now.

There is no single best way to implement Caring Contacts. There several methods and formats that can be used and the Practical Guide to Sending Caring Contacts walks you through selecting which are best for your setting.

Caring Contacts can be delivered by two-way text message to a large number of participants by a small team. The capacity of a Caring Contacts program is primarily limited by the ratio of follow-up specialist FTE available to support participants. To estimate how many participants your program might serve, you will need to make some assumptions about what proportion of eligible potential participants will enroll in the program. In the SPARC Trial, about 36% of eligible patients screening at risk for suicide were referred to the study by their Primary Care Physician/Provider or ED social worker, and 42% of referred patients went on to enroll in the study. Once these participants graduated from the study, they were offered the opportunity to continue receiving Caring Contacts in a non-research program. About 5% of SPARC participants opted to receive an additional year of Caring Contacts support. Enrollment rates in your organization may differ based on referring staff awareness and attitudes about the program, potential participants’ interest, and ease of enrollment workflows.

Program costs will primarily consist of cost of the intervention medium and personnel costs. Depending on which path you take, we expect you might encounter some of the following expenses.

Personnel Costs

Maintaining an appropriate ratio of interventionists to participants is key to ensuring personalized outreach and consistent message delivery in a Caring Contacts program. Previous work in the SPARC and SPRING trials have demonstrated that ~2.5 full time equivalent (FTE) for program staff/follow-up specialists are recommended for the first 1,500 enrolled participants. This ratio allows for appropriate coverage for all operating hours, flexibility in scheduling for anticipated or unexpected life events, and the ability to perform necessary daily work and quality control checks. Once this 1,500-participant threshold is met, an additional ~0.5 FTE for every additional 750 participants is recommended to maintain high quality care in the program.

For budgeting, teams should calculate the number of FTEs needed for the program and multiply by the cost per FTE.Who will send the messages and monitor for responses? Hint: We’ve found that it’s best for authors to have met the patient and established rapport and not be the one providing ongoing care.

Administrative Costs

If you choose to send messages via postal mail, your expenses might include office supplies such as paper, ink, envelopes, or stamps.

If you choose to send messages electronically, an organizational email account or cell phones will be required. Digital options such as Text message will incur per-message fees (often ten cents.)

If you choose to utilize the platform that we recommend in our Practical Guide, Mosio, it provides organizations with the flexibility to utilize a texting platform that can be custom built to best suit the needs of the organization. Our team worked with Mosio to develop a customizable templated build for two-way Caring Contacts. Assisted Setup of Customizable Build and Team Training $2,997*: Allows organizations to customize and use a templated two-way Caring Contacts standard build that our team developed with Mosio. This includes texting number registration, account configuration and customization, and virtual training sessions to introduce the dashboard and provide a detailed walkthrough for the functionalities included plus two-way texting & click-to-call services, and ongoing customer support for the duration of the project. This includes the first-year licensing fee of $XXX, which Mosio charges annually thereafter. Additional Programming Requests: Programing costs for add-ons to the standard Mosio dashboard may be extra. Contact Mosio directly for estimated cost for specific add-on requests that fall outside the scope of the standard setup. Fees may vary depending on program complexity.

(Costs above were quoted for the Caring Contacts Mosio build developed by St. Luke’s and University of Washington in June 2025.)

How much staff time required is highly dependent on group size and your chosen delivery method.

Caring Contacts is a scalable intervention. A low staff volume (1-2) can handle several hundred participants simultaneously. A staff of 2.5 can handle approximately 1,500 participants simultaneously, with an additional 750 participants per extra staff person added.

This is possible as numerous prior studies have shown only a small percentage of active participants actively engage with staff members at any given time.

Timing of message delivery can be custom tailored to only be sent at specific times of the day or week (i.e. during office hours) and participants can be notified not to expect replies afterhours in order to minimize any afterhours staffing requirements

Digital messages often require less staff involvement, while postcards or letters often involve more staff effort to hand write or print and send each message.

Caring Contacts authors don’t need a clinical degree or experience! In most two-way texting research, Caring Contacts authors were trained non-clinicians.

Clinician oversight (Social Worker, Psychologist, Physician, etc.) should be accessible to Caring Contact staff for any risk escalation that requires acute clinical support

During our previous trials, the majority of participant responses were positive or neutral, with some acknowledging challenges without expressing distress and fewer indicating acute distress. You can learn about what sorts of responses we’ve gotten in previous trials on the Examples page.

We have developed set of example legal agreements and Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to be used when partnering with other organizations, which your organization may adapt to fit your unique needs.

The Caring Contacts intervention can be feasibly implemented by organizations of all sizes and skill levels. This guide offers advice and recommendations for all phases of design, planning, and implementation, along with guidance on how to manage day-to-day implementation challenges.

Let's get Started

A simple intervention to reduce suicide deaths – written messages of compassion and empathy – showed promise in the 1960s, but has been overlooked until now.

watch here

Over the last few years, nobody, it seems, has been left untouched by suicide. We wanted to understand why that is. We also wanted to discover what could be done about it.

read hereThe original Caring Contacts study with postal mail in the US was replicated in a shortened 12-month protocol by researchers in Australia who sent postcards (in envelopes) to individuals who had been admitted to a toxicology unit for self-poisoning. Although there were no differences in the proportion of each study condition who were hospitalized for self-poisoning, there was more repetition of deliberate self-poisoning in the control group than among those receiving postcards. These differences persisted for at least 5 years. Other scientists replicated the postcard intervention in Iran with a sample of 2300 self-poisoners; with minor modifications including using floral greeting cards, including poetry stanzas, and sending a message on their birthday. Results found fewer individuals in the caring letters condition reported suicidal ideation and fewer made a suicide attempt.

Starting in 2016, Caring Contacts moved from postal mail to text message in a study with the US Army and Marine Corps. The format was the same as the postcard studies except using 11 brief text messages instead of a postcard or greeting card over one year. A typical text message read “Hi John, Hope everything’s going well. – Kate mcproj.org” or “Hello again, John! Hope things are good. Kate mcproj.org” (where mcproj.org is a website that provided military specific resources and the names and job titles of study staff). Results showed significantly fewer Marines and Soldiers in the Caring Contacts condition reported (1) any suicidal ideation and (2) any suicide attempts during the intervention year.

Text messages were also used in a comparative study of two different models of Caring Contacts sent to a sample of 666 patients and healthcare providers in a rural and frontier health system in Idaho, USA during the COVID pandemic. The goal of the study was to determine whether adding an introductory phone call – so that participants had spoken with the person texting them – improved loneliness, suicide risk, and other mental health outcomes. Outcomes were comparable between models, indicating that speaking with the Caring Contacts author did not significantly improve clinical outcomes for participants. Satisfaction with Caring Contacts was very high for both patients and providers.

Research focused on implementing Caring Contacts with veteran populations has also been conducted, and the findings on veterans’ preferences regarding the intervention can be found in these papers:

If you’d like to learn more about the research, see the references here

References