What Are Caring Contacts?

There’s a pressing need to quickly adopt scalable, technology-driven approaches for preventing suicide.

There’s a pressing need to quickly adopt scalable, technology-driven approaches for preventing suicide.

Caring Contacts (CC) is one of only two interventions that have been found to prevent death by suicide in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The original Caring Contacts intervention was developed by Jerome Motto in the late 1970s and guided by four principles.

The forces that bind us willingly to life are mostly those exerted by our reciprocal relationships with our environment and the beings in it, whether they be intimately involved in our lives or influence us by other psychological processes.

A suicidal person can be encouraged to retain an interest in continued living, by regular and long-term contact with another person who expresses caring about the former’s wellbeing.

The contact must be initiated by the concerned person and must put no demands or expectations on the other, in order to be experienced as an expression of unconditional concern and to have a potential for reducing feelings of isolation and helplessness.

Such a program of continuing contact can exert a long-term prevention influence on high-risk persons who cannot accept the established health care system or who have unmet needs. Long-term follow-up from an RCT comparing Caring Contacts to treatment as usual (TAU) found participants in the Caring Contacts condition had a lower suicide rate in all five years of the study and a significantly lower rate for the first two years.

Feeling suicidal is so much about feeling alone and feeling this will never change. Caring Contacts arrive periodically—weekly, monthly, bi-monthly—over a year or longer showing continued care, interest, and support with no effort from the recipient. Caring Contacts participants report that messages continuing to come over time have been healing for them.

Caring Contacts can also be a bridge to help someone ask for help who would not otherwise have asked. It is not uncommon for someone to reply to their 8- or 10-month Caring Contact with a request for help, resources, or a pathway back to treatment that ended months before.

Caring Contacts can be offered as aftercare following safety planning or hospitalization and has been used successfully with recipients from a variety of backgrounds - military, veteran, youth, native communities, primary care and emergency departments, healthcare providers, etc. - from around the globe including the US, Australia, and Iran.

Image credit: Jason Cherkis, Huffington Post, November 15, 2018. “The Best Way To Save People From Suicide”

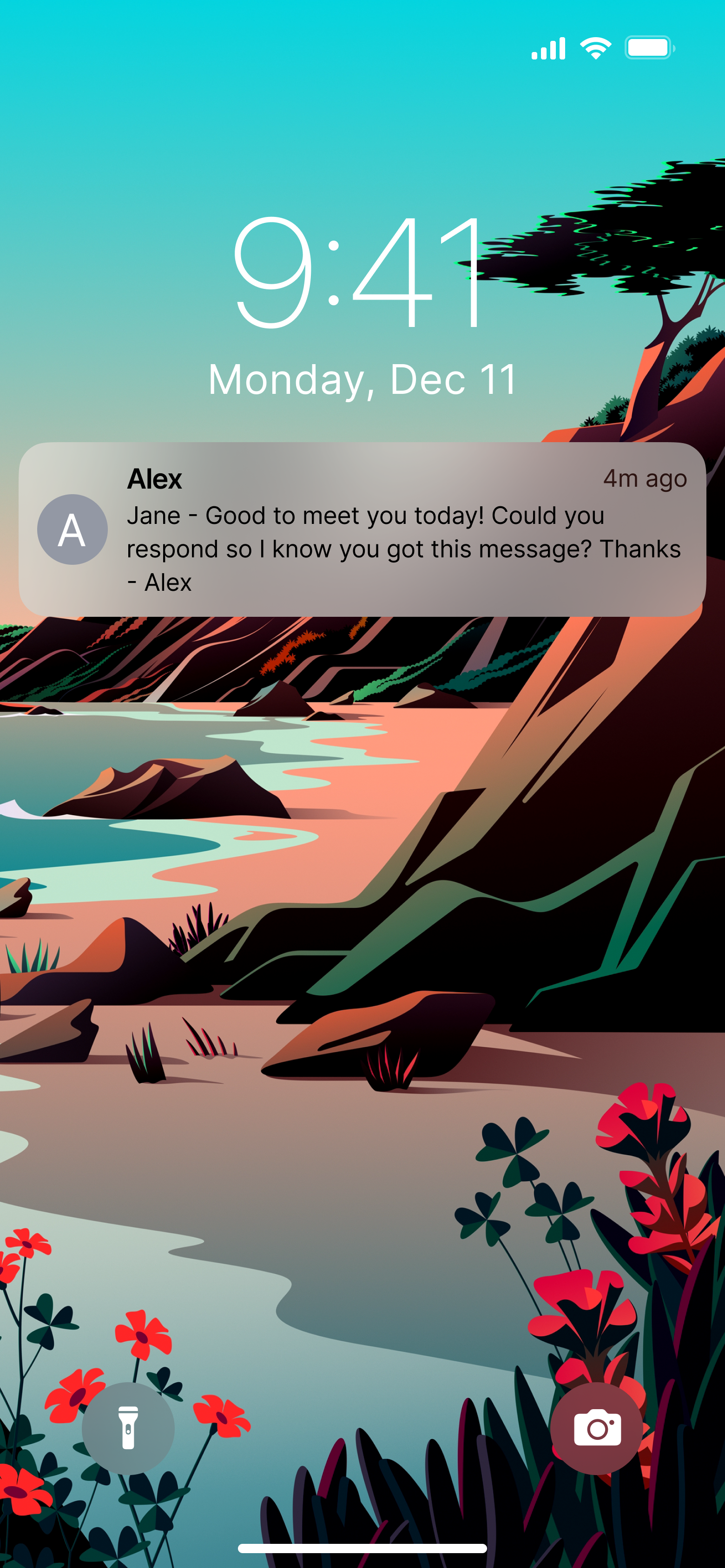

The importance of continued, long-term contact is evident in this image of what Motto referred to as “the bingo letter.” The participant in Motto’s trial who wrote this 5-page, single-spaced, typed reply to researcher Douglas Kreider had, 18 months earlier, written what Motto described as a “kiss off” letter to Mr. Kreider—basically an “I’m fine, thanks” response. In this subsequent letter, it is clear that the repeated and long-term quality of the letters was—at last—making an impact.

Feedback from previous recipients

“I actually enjoyed it, because I knew it wasn't just a computer, it was an actual message.”

“[The messages] made me value life more. Because life is valuable. It really is.”

“It helped me boost my confidence. When I was feeling down, there was somebody thinking of me and it made me feel better about myself, made me move forward. That's what those messages helped me with, gave me strength.”

“It was a good feeling to know that somebody is actually out there. Somebody thought about you today and decided to check on your wellbeing... it helped me to understand there are people that care out there. It's not just me by myself, that it's okay to talk to someone that I don't have to keep it all bottled up.”

Despite the strong support for the Caring Contacts intervention, very few health systems are using Caring Contacts. In addition, many have made maladaptive adaptations that weaken core Caring Contacts principles. These maladaptive modifications occur largely because the steps to carry out the intervention often fall outside of established workflows. There has not been an easily accessible guidebook for planning, initiating, and delivering the messages, until now.

There is no one way to implement Caring Contacts. There are a wide range of methods and formats that can be used and the Practical Guide to Sending Caring Contacts walks you through selecting which are best for your setting.

Depending on which path you take, we expect you might encounter some of the following expenses:

Who will send the messages or and monitor for responses?

Hint: We’ve found that it’s best for authors to have: have met the patient and established rapport and are not be the one providing ongoing care.

If you choose to send messages via postal mail, your expenses might include office supplies such as paper, ink, envelopes, or stamps. Digital options such as text message will incur per-message fees (often ten cents.)

How much staff time required is highly dependent on group size and your chosen delivery method.

Digital messages often require less staff involvement, while postcards often involve more staff effort to hand write and send each message.

Caring Contacts authors don’t need a clinical degree or experience!

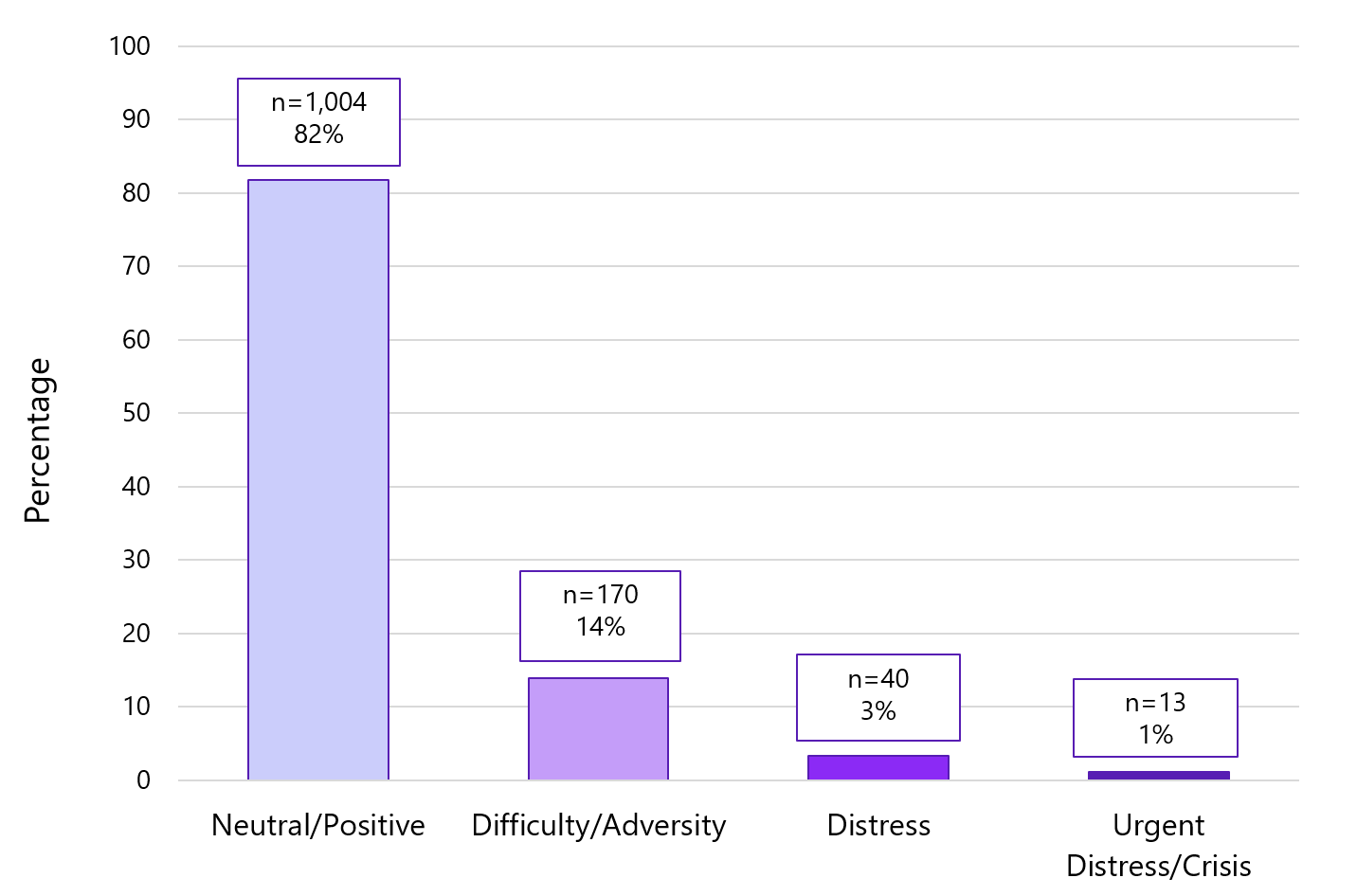

During our previous trials, the vast majority of participant responses were positive or neutral, with some acknowledging challenges without expressing distress. A handful of replies reflected mild discomfort, while only a few conveyed urgent distress or potential risk.

The Caring Contacts intervention can be easily implemented by organizations of all sizes and skill levels. This guide offers advice and recommendations for all phases of design, planning, and implementation, along with guidance on how to manage day-to-day implementation challenges.

Let's get Started

A simple intervention to reduce suicide deaths – written messages of compassion and empathy – showed promise in the 1960s, but has been overlooked until now.

watch here

Over the last few years, nobody, it seems, has been left untouched by suicide. We wanted to understand why that is. We also wanted to discover what could be done about it.

read hereThe original Caring Contacts study with postal mail in the US was replicated in a shortened 12-month protocol by researchers in Australia who sent postcards (in envelopes) to individuals who had been admitted to a toxicology unit for self-poisoning. Although there were no differences in the proportion of each study condition who were hospitalized for self-poisoning, there was more repetition of deliberate self-poisoning in the control group than among those receiving postcards. These differences persisted for at least 5 years. Other scientists replicated the postcard intervention in Iran with a sample of 2300 self-poisoners; with minor modifications including using floral greeting cards, including poetry stanzas, and sending a message on their birthday. Results found fewer individuals in the caring letters condition reported suicidal ideation and fewer made a suicide attempt.

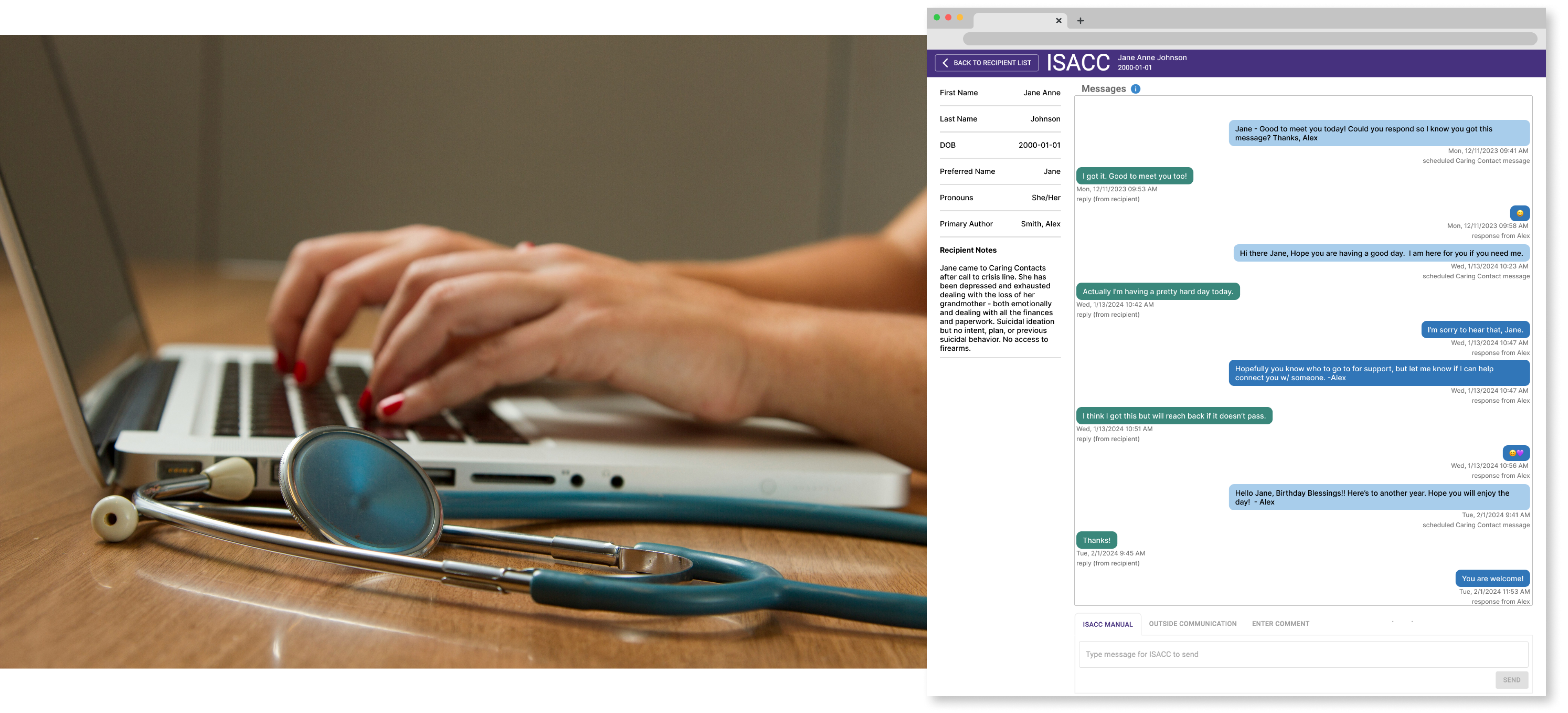

Starting in 2016, Caring Contacts moved from postal mail to text message in a study with the US Army and Marine Corps. The format was the same as the postcard studies except using 11 brief text messages instead of a postcard or greeting card over one year. A typical text message read “Hi John, Hope everything’s going well. – Kate mcproj.org” or “Hello again, John! Hope things are good. Kate mcproj.org” (where mcproj.org is a website that provided military specific resources and the names and job titles of study staff). Results showed significantly fewer Marines and Soldiers in the Caring Contacts condition reported (1) any suicidal ideation and (2) any suicide attempts during the intervention year. Text message were also used in a comparative study of two different models of Caring Contacts sent to both patients and healthcare providers in a rural and frontier health system in Idaho, USA during the COVID pandemic. Although outcomes were comparable between models, satisfaction with Caring Contacts was very high for both patients and providers.

Since that study, further research into implementing Caring Contacts with veteran populations has been conducted, and the findings on veterans’ preferences regarding the intervention can be found in these papers:

If you’d like to learn more about the research, see the references here

References